Friday, August 1, 2014

Friday, July 11, 2014

E.B. White's Only Book

Posted by

pinenut

at

7:19 AM

0

comments

![]()

Monday, June 9, 2014

Field Guide to Reading Discoveries

There’s lots for nature lit lovers to enjoy in a new anthology of book reviews, commentary, and interviews called Washington Independent Review of Books: A Sampler. Natalie Wesler critiques a new biography of Thoreau’s editor and sometimes-friend in Margaret Fuller: A New American Life, by Megan Marshall; Susana Trapani examines the breakdown of a fictional utopian community in the face of climate change and human nature in Arcardia, by Lauren Groffl; and Grace Cavalieri celebrates Because I Am the Shore I Want to Be the Sea and other outstanding poetry collections that explore our world—natural and otherwise.

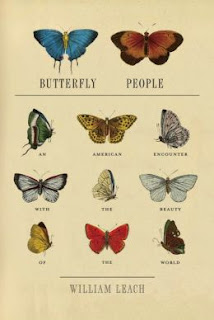

All of the selections first appeared in the insightful and often-surprising online publication Washington Independent Review of Books (WIRB). In 2011, even as traditional media cancelled book review sections, and shuttered bookstores curtailed browsing for new titles, WIRB launched its daily postings of pithy fiction, nonfiction, and poetry reviews, plus features about literary figures, trends, and controversies. David Stewart, president of WIRB, says each posting represents the site’s efforts to “poke your consciousness” and “tell you about ideas and adventures you’ve forgotten or never knew.” WIRB board members Kitty Kelley and Ken Ackerman, along with Stephanie Eller, have put together their favorite tidbits from WIRB online to create the appetizing print anthology, Sampler. In some ways, paging through the collection feels like falling down a rabbit hole—each brief piece opens up a world of reading possibilities beyond your wildest imagination. In fact, if you tried to read every work of the creative minds featured therein, you would go mad as a hatter. As a regular reader of the website, I was pleased to see some of my favorite reviews made the cut. Carrie Marden’s review is how I knew to put Amy Stewart’s The Drunken Botanist on my husband’s birthday list (Marden aptly notes that Stewart “makes the reader feel like a friend perched on the next bar stool”). The late Donald Carr’s review of Louis Agassiz: Creator of American Science is so tantalizingly detailed that I want to write about the erudite and flawed Agassiz myself. My review of Butterfly People: An American Encounter with the Beauty of the World is one of the selections in “Science and Culture.” By eminent historian William Leach, Butterfly People profiles leading lepidopterists and butterfly collectors of the 19th century, revealing aesthetic as well as scientific drives behind their obsessive acquisitiveness. Thinking about those zealous naturalists in the context of WIRB’s anthology reminded me of similarly obsessive book collectors. Just as butterfly enthusiasts know they cannot scoop up every iridescent winged insect, book lovers realize their reading time and shelf space are limited. But like a good field guide, WIRB’s Sampler and daily web reviews can be a lodestar in a literary universe with almost too many paths to follow and wonders to discover.

Posted by

pinenut

at

1:08 PM

0

comments

![]()

Friday, May 16, 2014

Geurilla Gardens of Nature Books

Free books? They’ll make your day if you happen upon them as I did yesterday morning. Free books in public places can promote literacy and build community too, according to Little Free Library.org. I was delighted to discover that one of their charming boxes has popped up in my neighborhood.

Peering inside, I noticed only about a dozen books—a Dan Brown novel, a classic children’s book, and other popular fiction, not my usual fare. But then I spotted Second Nature: A Gardener’s Education, by Michael Pollan. I started reading Pollan with An Omnivore’s Dilemma, his best-selling examination of our tangled and troubling food industry. But before becoming the leading critic of industrialized agriculture, Pollan was known as an adept, even dazzling, gardening writer. What more delightful way could I encounter his earlier work (which one reviewer says “is to gardening what Izaak Walton’s Compleat Angler is to fishing") than in a neighborhood garden’s free library? This particular little library is next to “The Other Barn,” a facility offering a safe place to hang out for teens after school. In contrast, our actual public library seems less then welcoming to youths' sometimes-raucous presence. A police officer guards the entrance at school dismissal time, and all couches have been removed to prevent loitering. Once, as I entered the library branch, a librarian warned me in a whisper, “Don’t stay long. Schools almost out!” The Little Free Library motto is “Take a Book, Return a Book,” and I went back today and tucked in a copy of a favorite teen book from my house--Megan Whelan Turner’s riveting historical fantasy, The Thief. I’ll be checking back, too, to see if it’s taken—and what surprise replaces it. Wouldn’t it be tremendous if Little Free Libraries welcomed people of all ages in all neighborhoods? LFLs have been created for all sorts of reasons—memorials, anniversary celebrations, recipe and seed sharing—so why not to spread the word about nature protection and even climate disruption? Wouldn’t this be a great way to pass around our extra field guides, essay collections, Rachel Carson biographies, etc? Every nature center should at least have a Little Free Library with a copy of A Sand County Almanac, free for the taking. Think of the riches that would be returned?

Posted by

pinenut

at

11:33 AM

0

comments

![]()